When Standard Patterns Fail: How to Know When to Break the Rules

Practical signals, safe ways to experiment, and how to prove it worked.

Practical signals, safe ways to experiment, and how to prove it worked.

Standard patterns exist for a reason: they reduce cognitive load, match user expectations, and speed up decision-making. Most of the time, you should use them. Sometimes… you shouldn’t.

This guide shows you how to tell the difference, with clear tests, examples, and a safe “break-the-rules” workflow your team can trust.

In This Issue

When Patterns Work… and When They Get in the Way

A Simple Test: 7 Signals It’s Time to Break the Rules

Safe Experimenting: The “Guardrail” Workflow

Concrete Examples (With Better Alternatives)

How to Sell a Rule-Break to Stakeholders

Resource Corner

When Patterns Work… and When They Get in the Way

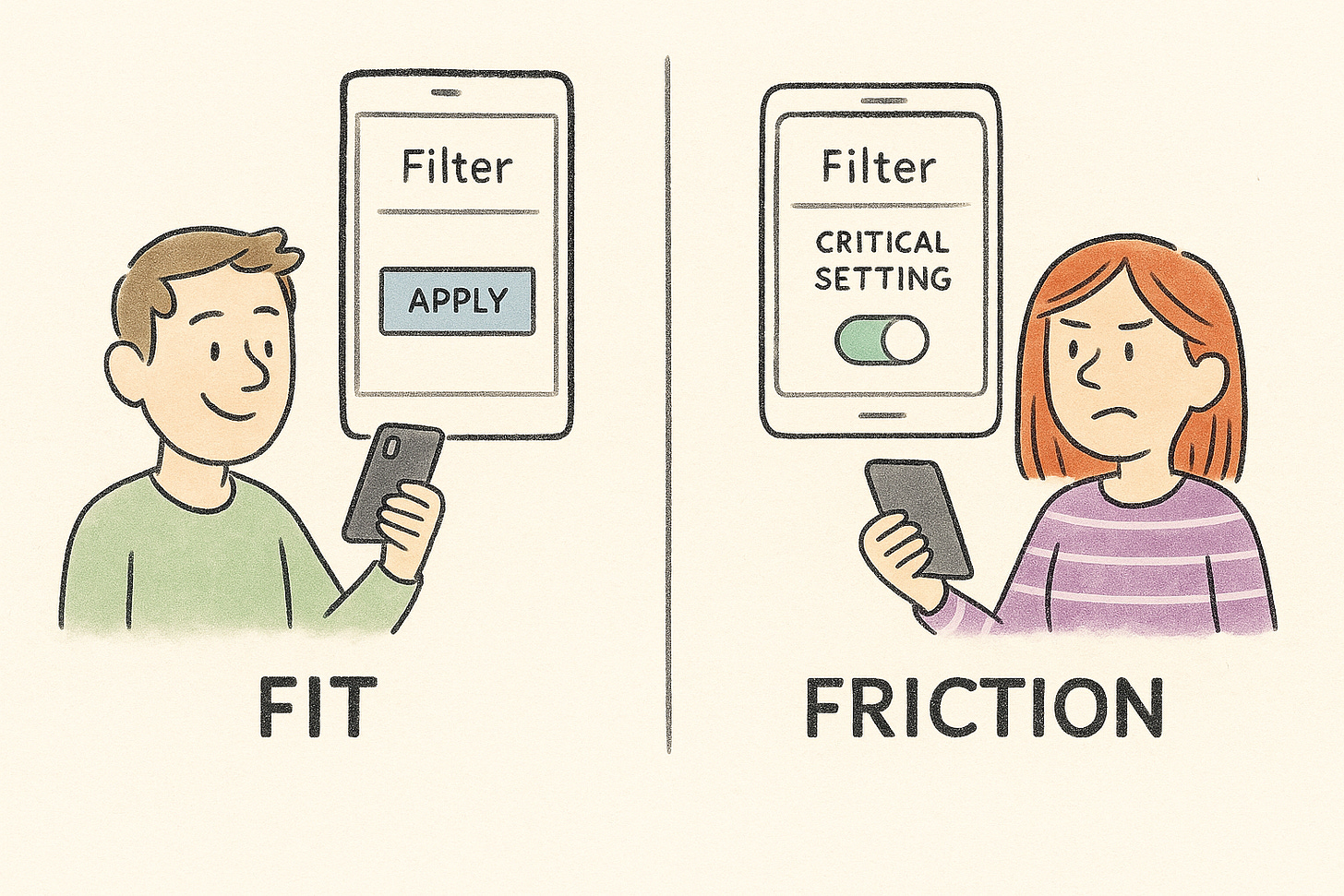

Patterns work when they align with established expectations: consistent labels, predictable locations, standard controls. They lower effort and help users transfer skills from other products.

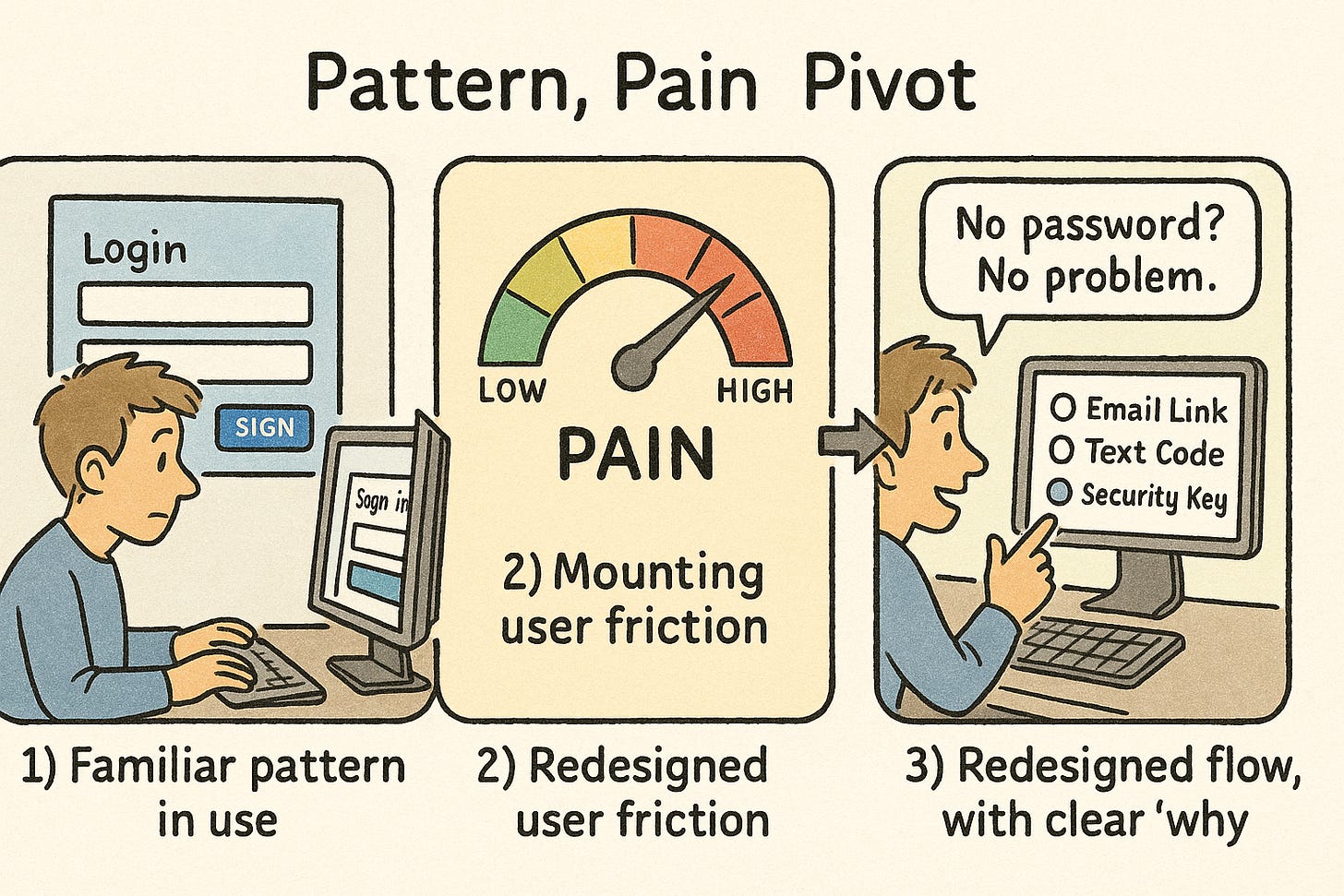

Patterns get in the way when the context has changed (new devices, constraints, or user goals), or when the “standard” creates avoidable friction. Design guidance should help you choose clarity over novelty… but also recognize when novelty is warranted.

A Simple Test: 7 Signals It’s Time to Break the Rules

Use these quick checks. If you hit 3 or more, explore a rule-breaking alternative.

Critical task is slower than it should be

If a common task takes multiple steps because of a pattern’s constraints, that’s a red flag.Users ignore or fight the pattern

Eye-tracking and scanning studies show people skim in predictable ways (e.g., F-pattern). If your “standard” sits where people don’t look, it’s not standard to them.Progressive disclosure hides vital actions

The technique is great for complexity… unless it buries something essential for most users.Defaults are doing the wrong thing

Users rarely change defaults. If the default is risky or suboptimal, the pattern is hurting outcomes.Your audience is expert or high-frequency

Experts benefit from optimized, sometimes unconventional flows that remove steps.New modality, old pattern

Voice, wearables, or spatial interfaces often break old screen-based norms; forcing them can increase errors.Design-system rule conflicts with real behavior

Design systems aim for consistency at scale, but they’re a means, not the goal. If the system pattern blocks a high-value outcome, it needs an exception.

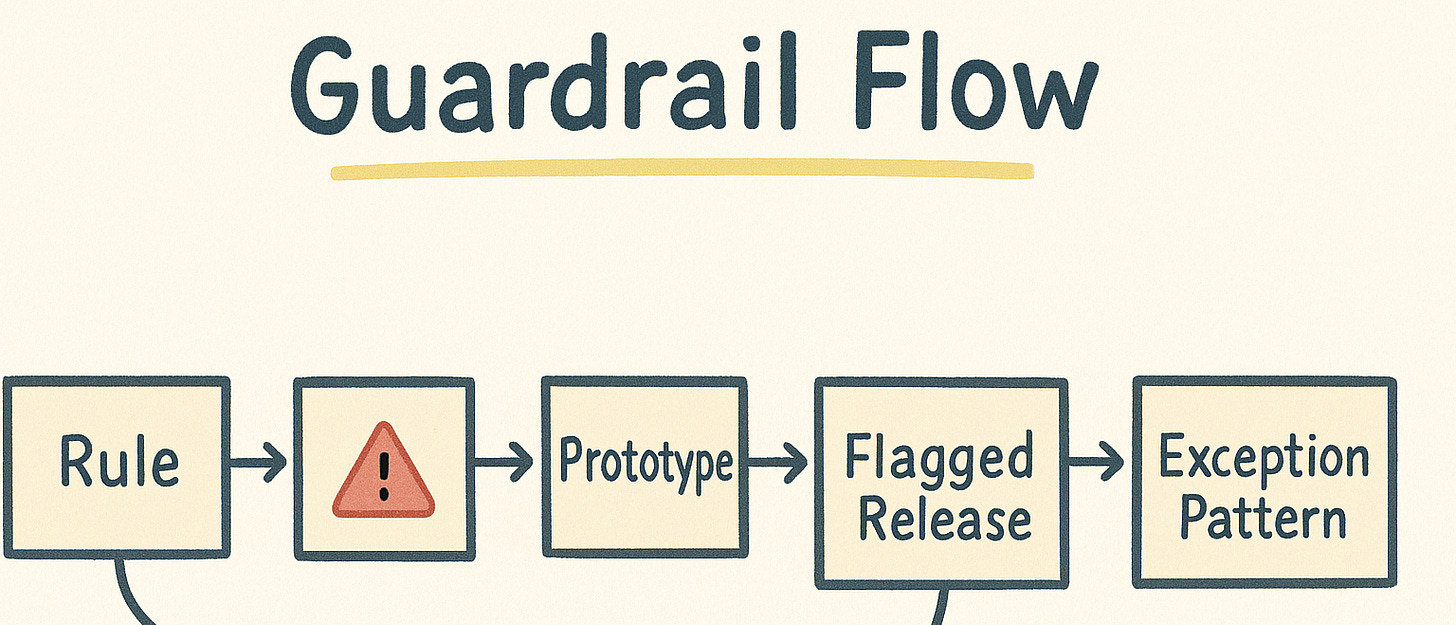

Safe Experimenting: The “Guardrail” Workflow

Break rules deliberately, not accidentally.

State the rule you’re breaking

Example: “We’re surfacing advanced filters by default, overriding progressive disclosure.”Define the harm the rule is causing

“Power users toggle these filters daily; hiding them adds three steps and boosts errors.”Draft a constrained alternative

Offer a narrow, testable change (not a full redesign). Keep copy and IA stable where possible.Prototype at the right fidelity

Low-fi for concept fit; higher-fi for interaction timing and microcopy, per NN/g guidance on fidelity.Test with the right users

Include novices and experts (or occasional vs. frequent users). Measure time to task, error rate, and satisfaction.Ship behind a flag

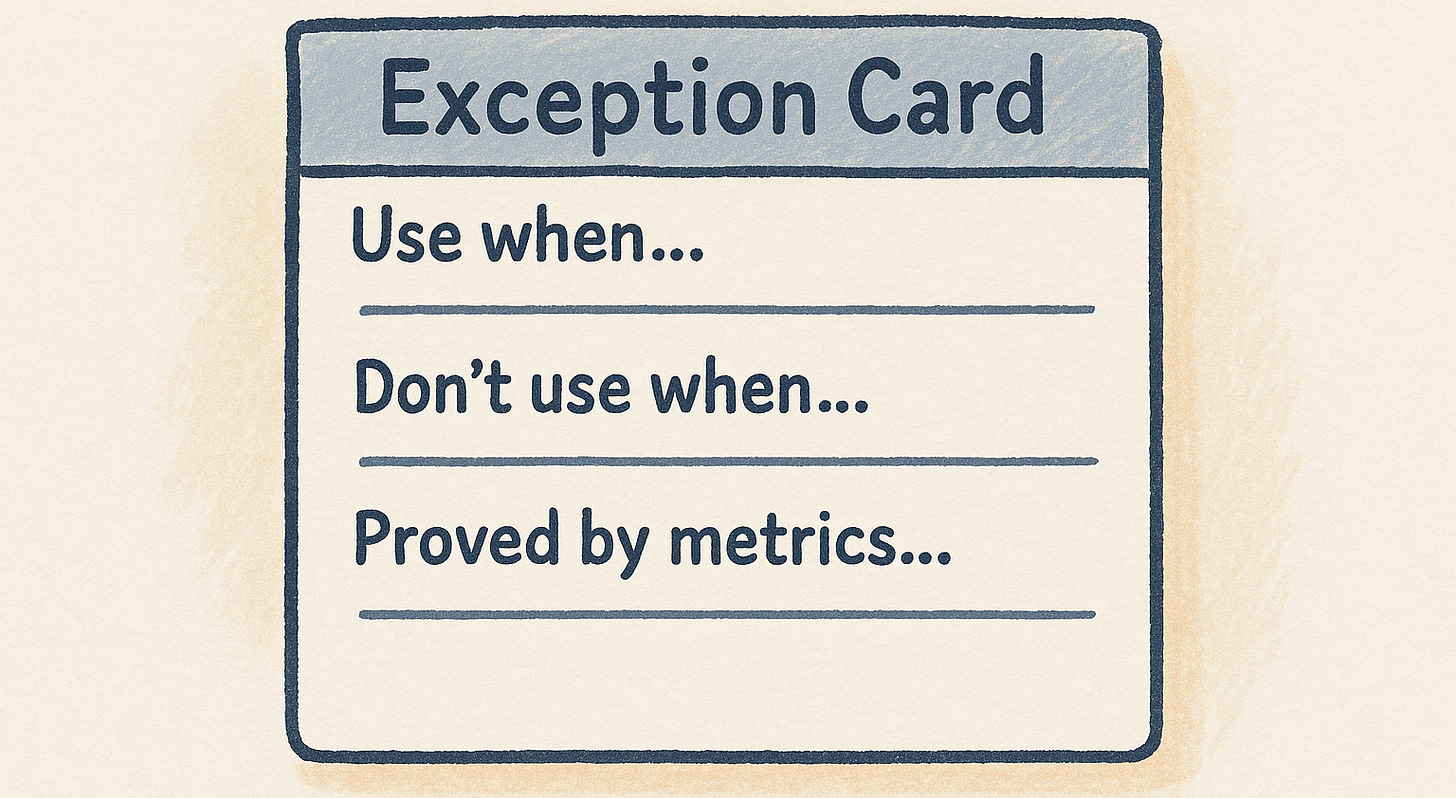

Start with a cohort that exhibits the pain (e.g., heavy filter usage). Monitor impact.Document the exception

If it works, write an Exception Pattern in your design system: when to use, when not to, metrics that justify it.

Concrete Examples (With Better Alternatives)

1) Hidden Advanced Filters

Pattern: Keep advanced filters behind a collapsed panel (progressive disclosure).

Problem: In B2B analytics, advanced filters are used every session; hiding them adds steps and increases mis-selections.

Alternative: Show the top 3 advanced filters inline; collapse the rest.

Measure: −25% time-to-query, fewer back-and-forth clicks.

2) Rigid Left-Nav in a Dense Tool

Pattern: Fixed, alphabetized left nav for “consistency.”

Problem: Users scan in patterns and prioritize a handful of frequent destinations; alphabetic order buries critical items.

Alternative: Task-ordered nav with a “Most used” cluster at top; keep a secondary “All items A-Z” view.

Measure: Increased findability and first-click success.

3) “Neutral” Default Settings

Pattern: Leave settings neutral to “avoid bias.”

Problem: Users rarely change defaults; neutral can be harmful (e.g., off by default for security prompts).

Alternative: Choose beneficial defaults and explain why; allow easy opt-out.

Measure: Fewer support tickets, better safety/compliance outcomes.

4) Strict System Rule vs. Critical Use Case

Pattern: Design system mandates a modal for confirmations.

Problem: In a rapid, expert workflow, modals interrupt flow and cause mode errors.

Alternative: Inline confirmations with undo; keep modal for destructive bulk actions only.

Measure: Faster task completion; no rise in irreversible errors.

How to Sell a Rule-Break to Stakeholders

Lead with the user harm and business risk

“This pattern adds 3 steps to a daily workflow; it drives 18% of support tickets.”Anchor to established principles… then explain the exception

“We follow consistency by default (NN/g heuristic). In this context, consistency reduces efficiency; here’s a constrained exception.”Show a small, reversible test

A/B a single cohort, behind a flag, with clear stop conditions.Report outcomes, not opinions

Time-to-task, error rate, satisfaction, support volume. If it wins, document the new Exception Pattern so the rule-break stays intentional.

Resource Corner

All links below are verified and working:

Final Thought

“Following the rules” is the default for good reason.

Breaking the rules is justified when the user harm is clear, the alternative is constrained, and the results are measured.

Start with standards. Listen for friction.

When the evidence says the pattern is the problem… change the pattern, and document the exception so everyone understands when and why to do it again.